Note: All items pictured on this website are in Frank W. Reiser's private collection. Please contact me to exhibit the collection at a secure institution or to seek additional information about the topics covered.

Documented Preserved Lung Tissue From the Kentucky Meat Shower of March 3, 1876

Specimen Mounted by Charles Finney Cox, Founding Incorporator of the New York Botanical Garden, President of the New York Microscopical Society and the New York Academy of Sciences.

Navigation Links

Overview

Full story

Could it be a hoax?

Firsthand expert opinions

Testimony of Rebecca Crouch

Discussion: notable microscopists

who examined the meat specimen

OVERVIEW

On a sunny morning in Mud Lick, Kentucky, in 1876, a half-bushel of bloody chopped internal organs fell from the sky onto a woman and her ten-year-old grandson as they worked in a yard near their farmhouse. Panicked, the two ran from the gooey downpour into the house, slammed the door, and hid. Soon after, curious neighbors came to view the gore-draped landscape, which also worked as a chum slick, bringing in the local press. Word of the uncanny meteorological event quickly spread nationally, reported by newspapers from New York to San Francisco. The headlines named the event the Kentucky Meat Shower, further reinforcing the state’s foreboding Civil War moniker, “a dark and bloody ground.”

Curiosity seekers collected and examined fragments of what fell on the Crouches’ Bath County farm. A few samples were sent to knowledgeable and respected individuals for further study, hoping their expertise would illuminate the true nature of the material and provide an explanation that resolves the mystery. A few bold neighbors tested the unknown substance at the site, picking up pieces, sniffing, chewing, and inevitably spitting them out. The New York Herald reported that one amateur sleuth was brought to the brink of hysteria. He claimed his left arm became paralyzed after touching a piece, and it hung by his side, immobile, for an hour. The journalists visiting the scene cross-examined witnesses and a spectrum of locals—from chemists, hunters, and other unquestionable experts on lumps of meat, such as the town’s butcher—how could such strangeness occur? Others, not inspecting the scene themselves, crawled through library shelves, searching for similar historical occurrences or prophecies that could shed light on which guiding hand might have directed the sanguine dump.

The first experts to publish their analysis of samples of what fell on the farm surmised in the press that “everyone was wrong”; it was not meat at all. One reported the specimen they examined to be globs of reproductive spawn having been chucked to the breeze by amorous frogs. Another emphatically declared the specimens were not animal-related at all, but a primitive type of plant life classified by biologists as algae.

The investigation that unfolded among a small but national community of microscope enthusiasts is the best part of the story. In the absence of central administration, avocational microscopists self-organized what is now called the scientific method through an exchange of letters. The story of their work illustrates the development of scientific thinking in the nineteenth-century United States.

The following webpage documents the modern-day discovery of a microscope slide that preserves a piece of meat that fell on the Crouchs’ Kentucky farm in 1876. It documents the process of the specimen’s authentication and depicts the chain of individuals (chain of evidence) handling the specimen, bringing it to a New York collection and exhibit.

THE FULL STORY

The Kentucky Meat Shower: Clear Sky, Bright Sun, Occasional Bloody Sprinkles

(I had) A vague idea that my husband and son, who were away, had been torn to pieces and their remains were being brought home to me in this way.

–Rebecca Crouch (farm’s owner and witness)

It was a morning like many others on the Crouchs’ Mud Lick, Kentucky Farm. The year was 1876, the season was late winter. A sunny, clear blue sky promised to chase away remnants of ice from the last night’s dip into the higher twenties. Allen Crouch, a farmer in his sixties, had just left with his thirty-four-year-old son, William, for a trip to the newly established town of Frenchburg. William was visiting his parents and brought his twelve-year-old son, named Allen after his grandfather. He left the boy with his grandmother, Rebecca, until their return. Rebecca and her grandson went out into the farmyard to begin their daily chores. And then the day turned into one unlike any other. (Herald, May 1876)

About an hour before noon, Rebecca was building a fire beneath a cast-iron vat she used for making soap. Allen was playing nearby when he suddenly exclaimed, “Hey, Grandma! It’s starting to snow,” and just as he did,

A lump of red, bloody, meat-like material hit the ground with an attention-getting splat. Rebecca looked up at the cloudless sky and saw hundreds of particles, looking like bloody spitballs, falling through the air. They ranged in size from hailstones to strips several inches long descending over a football field-sized area. Rebecca grabbed her grandson’s hand and ran for the farmhouse.

A week later, during an interview with a reporter from the New York Herald, Rebecca confided that seeing lumps of falling flesh shook her to her very core. She believed something terrible had happened to her husband and son. To Rebecca, the bloody rain of guts was pieces of her loved ones that “somehow were finding a way to come home.” As extreme as that fear may seem, Rebecca’s gory imagery was grounded in the reality of having witnessed past horrors. Only twelve years prior, in July of 1883, the Crouch’s farm – including adjacent farmlands – served as the combat field for one of the Civil War’s bloody cavalry battles – the battle of Mud Lick.

Once inside the farmhouse, Rebecca, her grandson, and a boarder, Miss Robinson, watched fearfully from a window. Robinson was a Bath County public school teacher who stayed at the Crouch farm during the school year. She described the meat shower as “falling in clumps and not evenly scattered like one sows oats.” Robinson stated that after collecting herself, she left the farmhouse to get a better view of what was going on. Unfortunately, the carnal downpour had stopped by the time she got out the door. Robinson looked about and saw meat hanging from brier bushes, fence rails, and lying on the ground. She also saw, with great surprise, the farm’s hogs and chickens gobbling up the bits of flesh as fast as they could find them, adding, “They sure seemed to like it very much.” Rebecca did not go back outside. She refused to leave the house until he husband and son returned from Frenchburg.

Also in the farmhouse was Sadie Crouch (1849 – 1939); the Crouches’ adult daughter was there but stayed in bed, feeling too sick to leave. As a result, even though present, she missed out on being a witness to the meat falling from the sky.

News about seemingly supernatural events spread quickly. Curious neighbors and folks from the nearby town of Frenchburg began crawling about the farm searching for souvenirs, making the meat shower, unlike other occult happenings, an event that left behind an estimated half-bushel of evidence. A lump of bloody meat was reportedly found inside someone’s shoe left outside on the farmhouse porch.

Mr. Armitage, a resident of Frenchburg, told the reporter from the Louisville Courier-Journal that when he touched the meat, he “felt a shot in my arm that left it paralyzed, hanging by my side for half an hour.” In contrast, a few of the emboldened put pieces in their mouths, chewing them to see if they could identify a flavor. The owner of the town of Mt. Sterling’s butcher shop, identified by the Courier as Mr. Frisbe, tasted one of the alien droppings and declared, “I can not tell what kind of animal it came from, but it is animal meat without a doubt!”

Another neighbor, Mr. Eli Wills, took an exploratory taste of the unknown material to an extreme. He gathered a hefty handful of meat and brought it home, intending to cook and eat it. Wills’ family members, fearing that the mysterious flesh might be poisonous or, even worse, cursed, tried to talk him out of it. But no. Wills had dug in his heels and would not abandon his gustatory aspirations. So, several family members physically held him down while another ran off with the meat and threw it in a place where they confidently knew he would not go to retrieve it when released. (Stack County News 1876)

Locating the Kentucky Meat Shower and the Crouch Farm Newspapers reporting the Kentucky Meat Shower at the Crouch farm only approximate its location. They describe it as being south of Olympian Springs. Other press reports reveal that the Crouch’s had a grandson in 1876 – information that provides an approximate age range for the couple. In a New York Herald interview, Mrs. Crouch mentions that their daughter, Sarah, was home when the meat shower occurred. Therefore, using those two bits of data as limiters, searching genealogical databases yields a solid Match to the family of Allen T. and Rebecca Crouch. An 1881 Bath County property map shows A. T. Crouch as the owner of a large farm with five structures along the Clark Fork of Salt Lick Creek. The location is on the southeast side of Kentucky State Road 36 and south of Pine Grove Road. The online genealogical data bank, Find-A-Grave, shows Allen’s grave marker in the Upper Saltlick Cemetery. Rebecca is resting nearby in a separate plot. Sarah died in 1941 at the age of ninety-two.

Joe Jordan’s statement to the NY Herald

I brought about two ounces to Mount Sterling and gave half to Capt. Bent. But Bent spat it out before he could taste it. The specimen was a week old and had a strong offensive smell. (Herald 1876)

Sometimes journalists may struggle with the temptation to embellish stories to make them more engaging. However, one consistent fact about the mysterious happenings at Crouch’s farm is clear. All of those who first visited the scene were unanimous: what was scattered about the property was undeniably meat.

Samples of the earth-fallen, suspected carrion were collected at the farm to be given to experts for analysis. Mr. Venarsdelle, who resides near Frenchburg, reportedly collected 15 or 20 samples. Allen Crouch gathered up a quantity as well. To save them, some pieces were allowed to dry, while others were jarred in alcohol, vinegar, or glycerin for their preservation. What remained was eaten by hogs, chickens, and wild birds. (Formaldehyde was not used to preserve biological materials or cadavers until after 1890.)

The first opinions to hit the press

The Prof. Robert Peter of Lexington, who obtained samples of what fell on the Crouch farm and provided samples to other scientists, concluded that it was animal flesh. He claimed the probable stated the cause to be in a very professorial manner. To be post postprandial disgorgement. In other words, Vultures ate too much and vomited on Rebecca Crouch. This was the most reasonable explanation at the time and the one that remains the prominent explanation to this day.

Those who were first on the scene to examine what fell to earth during the Kentucky Meat Shower stood gob-smacked when reading the opinions of experts in the press. J. Lawrence Smith, Professor of Medical Chemistry and Toxicology at the University of Louisville, claimed the samples from Crouch’s farm, given to him by Mr. Venardsdelle, were not animal flesh at all! With a dismissive tone, he identified the earth-fallen mystery to be blobs of toad or frog spawn – a mélange of amphibian ejaculate and eggs blown by the wind from a nearby pond. ( Courier-Journal 1876)

Two months later, a second opinion was published by Leopold Brandeis, a New York water treatment specialist, in the public health journal The Sanitarian. Brandeis, who received samples from Charles Thurber, editor of The Agriculturist, opened his response somewhat arrogantly by proclaiming, “The mystery of what happened on the Kentucky farm is now solved!” Brandeis states, “It is nothing more nor less than balls of algae known as Nostoc, well known to the old alchemists as ‘a low form of vegetable existence.”

Brandie sent a copy of his article to the editor of Scientific American, where it was reprinted, distributing Brandeis’ claims to a far greater readership, particularly scientists and microscopists. (Brandeis, June 1872)

The specimens Smith and Brandeis possessed were later verified to be pieces of meat. Unfortunately, the proposed explanations were based solely on historical literature reviews, which were both cited in their writings as validation. They used neither magnified vision nor chemical analysis. Their observations were limited to gross appearance and finger feeling the material, which they called a greasy blob. To err is human, but Smith’s and Brandeis’s highfalutin tone makes it difficult to excuse their myopic attempt at authoritative analysis. Both authors stated that anyone historically cognizant of past natural events would quickly explain the Kentucky Meat Shower as a well-known event. To their credit, though, Smith and Brandeis did save the samples on which they based their opinions and provided them to others who later questioned their findings. Smith retracted the findings, but a response from Brandeis has not yet been found.

Dr. Kastenbine, J. Lawrence Smith’s Former Student, Contradicts His Old Boss.

Dr. Louis Kastenbine was a medical doctor, chemist, microscopist, and resident of Louisville. He examined a sample of the meat-like material collected at Crouch’s farm by Blackburn via the pharmacist Simon Jones and published his opinion in the Louisville Medical News in 1876. Kastenbine burned a piece of the substance, sniffed the smoke, and stated, “It smells distinctly like mutton.” Kastenbine also examined the material microscopically and, concurring with Edwards’s claims, asserted it was definitely animal tissue.

The first theory put forth

A Forensic Expert Accepts the Challenge

Hamilton was both a medical doctor and an attorney. With expertise in two fields, he gained fame in the press by serving as an expert witness in several high-profile judicial cases. Hamilton was the first to write an authoritative book on delivering medical testimony in legal matters and is therefore known as the father of forensic science. Through experience, He knew the importance of seeking out the most authoritative experts to educate juries. In keeping with his forensic philosophy, when he received the Kentucky meat shower specimens from Chandler, Hamilton enlisted the help of one of the most prominent histologists available, J.W.S. Arnold.

Arnold was chair of the Department of Anatomy and Histology at the University of New York. His specialty was the preparation of microscope slides from human tissues and the identification of histological samples. Arnold created microscope slide mounts using samples from the Kentucky Rain Shower that Hamilton obtained from Chandler. After studying the slides, he stated they were, without a doubt, lung tissue. Hamilton also examined the slides under a microscope and agreed with Arnold’s conclusion.

The two doctors, Hamilton and Arnold, published their report in the New York Medical Record, stating that the specimens sent were, in fact, pieces of an animal’s lungs. Edwards read the Hamilton and Arnold paper and, as with Brandeis, asked the authors to send him the samples they worked with, which they did. Edwards confirmed Hamilton’s and Arnold’s identification of lung tissue.

Arthur Mead Edwards assumes the role of senior scientist.

The physician and microscopist Arthur Mead Edwards was President of the Newark Scientific Association, an organization open to professional and lay scientists. The group held weekly meetings to discuss current advances in the natural sciences. The Kentucky Meat Shower was one of the topics that caught the membership’s attention, particularly after Brandeis’ article in The Sanitarian was reprinted in Scientific American Supplement on July 1, 1876. Edwards knew Brandeis from the New York Microscopical Society and asked him to share samples of the materials on which he based his opinions so he could independently verify his conclusions. Brandeis gave Edwards all of the meat he had. Edwards, having read the published conclusions about the Kentucky Meat Shower by Alexander Hamilton and W. J. S. Arnold, wrote to Hamilton asking to be sent pieces of what they used for their work.

Edwards then prepared Canada balsam-mounted microscope slides based on what the two gave him. His microscopic examinations showed that the identity of the specimens given to him by all three were animal lung tissue. Edwards’ finding confirmed the identification of Hamilton and Arnold and challenged Brandeis’ claim regarding Nostoc algae.

Edwards was determined to provide a definitive answer as to what fell on Crouch’s farm on May 3 of that year. He next visited John Phin, editor of the American Journal of Microscopy, to examine the prepared microscope slides of Kentucky Meat Shower for the prepared slides he believed to have in his possession. One slide was prepared by W. H. Walmsley, Secretary of the Philadelphia Microscopic Society, Philadelphia, PA, and the other by A. T. Parker of Lexington, KY. Edwards confirmed that both slides contained striated muscle.

Moving down the list of those who corresponded, having possession of meat shower specimens, Edwards solicited A. T. Parker, in Kentucky, for the specimens he held. Parker mailed the material to Edwards, Capt. J. M. Bent had given him. Edwards noted that some of what he received was in a natural state (most likely dried), while others were preserved (undefined). After preparation and microscopic examination, these tissues were identified as cartilage, striated muscle, and connective tissue.

Arthur Mead Edwards’s self-created role would be described today as that of a senior researcher. He nailed down the identity of the stuff that rained down from the heavens onto the heads of Rebecca Crouch, and her grandchild was meat! His careful recording of the origin of each specimen provided the data needed to create the chain-of-custody flowchart included in this work. Additionally, Edwards embedded the samples he acquired in Canada balsam on microscope slides – a preservation technique as eternal as if trapped in amber. Edwards published the results of his microscopic analysis in the July 22 issue of Scientific American Supplement. Edwards’s work leaves little room for doubt that animal flesh fell from the sky upon Rebecca and her grandson Allen on March 3, 1876.

The tissue on the slide is consistent with the general structure of lung tissue. The clear areas are the small airways, called alveoli, and the dark red circular structure at the upper left is a blood vessel. The cells of the respiratory epithelium look relatively uniform, suggesting this might be from a healthy or non-pathologically affected lung. Nothing seen as indicative of the animal species from which it came, and since proper chemical fixation of the tissue had not been carried out, cell size and shape can not be trusted.

What if it’s all a hoax?

The Pranking Grandma Scenario

YouTube version available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8z3W2XidglI

A Skeptic Registers Her Doubts

Which hypotheses would Ockham pick to explain the Kentucky Meat Shower?*

- An adult and a child were working with meat scraps threw some in the air and said “it’s snowing” and the adult freaked out.

- A flock of vultures flying overhead vomited

- A miraculous warning from God of a coming calamity

- Pieces of dinosaur falling to earth from colliding asteroids

- The testing of a secret weapon by the government

- A balloonist lost his lunch

All the above were printed in the newspapers as possible explanations for the KMS

EXCEPT THE FIRST!

Meat Specimen at Monroe Moosnick Medical and Science Museum At Transylvania University,

Another mystery linked to the mysterious meat shower event

How can authenticity be determined?

Notes: The Kentucky Meat Shower occurred in 1876. The bottle was made by Schaar Chemical Co. Chicago which opened for business in 1906 – 30 years later. Bottle stoppered with a new cork. Top photo shows version with stained preservative. The second shows clear preservative.

Formalin was not used as a specimen preservative in the United States until after 1895.

Courtesy of Kurt Gohde, Transylvania University Medical Museum

Two Other Unexplained Meat Showers During the 1800s

Bloody Downpour in Tennessee

Sanguine showers have happened before and after the Crouch incident. Thirty-five years before the Kentucky Meat Shower, a similar atmospheric anomaly occurred in Tennessee. While working in a tobacco field, two farmhands heard a rain-like puttering from the leaves of the surrounding plants. The sky was cloudless and blue. Looking down, they saw the tobacco leaves were blood-splattered with small strips of flesh sticking here and there. The carnal scene stretched for hundreds of feet in all directions. The workers fled and fetched the plantation owner, Mr. F. M. Chandler. (Unrelated to C. F. Chandler) Chandler visited the location, gave the tobacco leaves a quick look-over, and hurried off to gather a few others to witness what happened and help figure out how such a bizarre thing might have come about. He returned with two well-known members from the nearby town of Lebanon, Mr. D. S. Drew and Mr. J. M. Peyton. They helped Chandler search the tobacco field and estimated that the bloody tidbits covered a circular area about 200 feet across. The largest piece of flesh they found measured 1.5 inches long by 0.5 inches wide. It seemed composed of muscle and fat and carried a rank odor.

According to The Spirit of the Times, on August 15, Dr. Sayle of Lebanon inspected the site of the bloody rainfall at Chandler’s plantation. He collected specimens and sent them to a person he described to the journalist representing The Spirit of the Times as “the most intelligent man I know.”Dr. Gerard Troost (1776 – 1850) was at the University of Tennessee at Nashville. Troost was a geological science professor and held the title of State Geologist for Tennessee. (Rooker 1932) Troost examined the specimen and revealed that the substance was a bloody piece of meat. But he also added that the examined flesh and blood “were of this world,” a statement aimed at vocal theorists who claimed the event signaled the End Times were coming. (Maxwell 2012)

Meat Blobs Fall From the Sky in North Carolina

On a cloudless day, just before noon, a sharecropper in Chatham, North Carolina, Mrs. Bass (Kit) Lasater, stood outside her home adjacent to a newly plowed field. She heard splattering sounds for about a minute, perhaps slightly longer, but felt nothing falling directly on her. Looking down, she saw the soil littered with small, bloody pieces of meat. She ran and told the others living in nearby cabins. Curious neighbors visited the farm where the blood had just fallen, and a few collected samples to show others or to keep hoping they would become religious relics. An unknown person brought pieces of the fallen flesh and blood-stained soil to two of the town’s physicians, Dr. S. A. Holleman and Dr. Sidney Atwater, for their learned opinions. (Chatham Record 1884, Meekins 2020)

Unfortunately, neither Atwater nor Holleman recorded the identity of the person who collected the material from Mrs. Lasater’s farm or the person who brought the material to the doctors. Dr. Atwater, seeking a different opinion in assessing the collected substance, dropped off what he had at the laboratory of Francis P. Venable (1856 – 1934) at the University of North Carolina. Unfortunately, the professor was occupied with another project and did not have time to check the samples until three weeks later. However, when he did return to the specimens, he undertook the identification task with great diligence. Venable even visited the site of the bloodshed in Chatham. By then, three weeks had passed, which included several rainfalls. While there, he met with the bloody rainfall’s sole witness, Mrs. Bass (Kit) Lasater, but even with her help, the two could not find any remaining evidence. (Wilson Advance 1834 )

In a published paper, Venable stated that the samples from the farm he had come from were from “two intelligent men,” but he mentioned only Atwater in his oral presentation to the Society. His results were based on analyzing cold water that had percolated through soil samples. First, Venable microscopically examined the leachate and found it contained identifiable red blood cells. Following that, he analyzed the leachate spectroscopically and observed spectral lines consistent with those expected for hemoglobin. The professor’s findings left little doubt about the soil samples harboring blood. In his paper’s closing remarks, he made clear that the findings did not prove that the bloody rainfall happened. He cautioned that the test results would have been the same had the samples come from a similar location where a pig had recently been slaughtered. (Venable 1884)

The Testimony of Rebecca Crouch

Dictated to the New York Herald on 03/21/1876

On Friday morning, March 3, between the hours of eleven and twelve o’clock, I was in my yard, not more than forty steps from the door of the room in which we are now sitting. ‘The skies were clear and the sun was shining brightly. There was a light wind coming from a westerly direction. Without any prelude or warning and exactly under these circumstances, the shower commenced.

The fall was not less than one nor more than two minutes in duration. I never touched any of the flesh until my husband came home. I noticed little whirlwinds in the mountains during the morning and predicted rain from that fact. When the flesh began to fall, I said to my grandson, who was the only person in the yard with me at the time, “What is that falling, Allen?” He looked up at me and said, “Why, Grandma, it’s snowing.” I then walked around and saw a large piece of it strike the ground right behind me with a slap when it struck. A vague idea that my husband and son, who were away, had been torn to pieces and their remains were being brought home to me in this way by the wind flashed through my mind at the moment. I was also impressed with the conviction that it was a miracle of God, which, as yet, we do not understand. It may have been a warning, as coming events are said to cast their shadows before them. The largest piece that I saw was as long as my hand and about half an inch wide. It looked gristly as if it had been torn from the throat of some animal. Another piece that I saw was half-round in shape and about the size of a half-dollar.

HOW THE PRESERVED, SLIDE-MOUNTED SPECIMEN WAS FOUND

Six boxes of microscope slides, collected and mounted by Jacob D. Cox, were found in Auburn, Ohio. Jacob D. Cox was a Civil War general, Governor of Ohio, and president of the American Microscopical Society. The boxes, each holding twenty-five slides, were individually offered on eBay. I submitted winning bids for five of the six boxed collections. A person with deeper pockets than mine won the sixth. However, the seller pulled several slides from the collection to list individually on the auction site. (offering unique slides as separate bid items can maximize profits.) The Kentucky Meat Shower slide was one in that category, being unique as it was made by Jacob's brother, Charles Cox. Apparently, The label identifying the specimen as a sample from a Kentucky Meat Shower seemed nonsensical to the seller. So, they assumed "meat" was an abbreviation for meteor and advertised the slide as holding a specimen from the "Kentucky Meteor Shower."

My competitor (in bidding only, otherwise deeply respected), Brian Stevenson, Ph.D. (Univ. of Kentucky), won one of the Cox slide boxes but missed the deadline to bid on the Meat Shower slide because of a meeting. As he described it,

I was at a conference at the time that the auction ended. I recall exactly where I was when I remembered the auction, and my anguish when I saw that it had ended several minutes before I checked!

Stevenson has one of the world's most extensive collections of antiquemicroscope slides on our planet. He missed getting the meat slide but did copy the slide's picture from the eBay auction site and post it on his website, thereby documenting its accession to the collector community in 2014. (Stevenson 2022)

Two Fun Online Sites About the Meat Shower Story

Rachel Madow reported on the Kentucky Meat Shower on her news show on January 7, 2011. The transcript is here: https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna41157190

Basti B’s website ‘Fringe History’, https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/basti-b0/episodes/Case-11-Kentucky-Meat-Shower-of-1876-e28mk7a

Mick Sullivan reads his own book, ‘The Meatshower,’ for Storytime with The Courier Journal, https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/basti-b0/episodes/Case-11-Kentucky-Meat-Shower-of-1876-e28mk7a

BIOGRAPHIES OF THOSE INVOLVED IN SOLVING THE KENTUCKY MEAT SHOWER MYSTERY

William Schmidt Arnold (1846 – 1888) was a professor at the University of New York, serving as chairperson of the medical school’s Department of Physiology and Histology. His specialty was the staining, slicing, and microscopic study of animal tissues. Alexander Hamilton’s assessment was on target when he asserted in the New York Medical Record that J. W. S. Arnold was the best person in the US to identify evidence collected at the site of the Kentucky Meat Shower.

J. W. S. Arnold was best known for his testimonies before the U.S. Congress and health-related agencies regarding his research findings on the safety of oleomargarine as a butter substitute. In the 1882 issue of the American Monthly Microscopical Journal, he stated that he taught practical histology at the University of New York for fourteen years. Arnold developed an interest in the emerging field of photomicrography to the point that he advertised his services as a photomicrographer in several journals. He was elected to a term as secretary of the New York Microscopical Society and was also active in several photography associations. Arnold’s photomicrographs received excellent reviews, and a collection of his prints is available in the Otis Historical Archives at the National Museum of Health and Medicine, Silver Springs, Maryland.

Not much information is available about Arnold’s personal life. Still, it appears that his retirement from the University at the young age of forty was related to failing health, as he died two years later. After retiring, Arnold continued using the University as his address, indicating a continuing association with the lab he once supervised. (Arnold 1882)

Capt. J. M. Bent (1837 – 1907). Bent was the proprietor of Aden Springs and Park, located in Mt. Sterling, KY. The Springs was a summer resort situated ninety miles east of Lexington but less than ten miles from Allen Crouch’s farm. Advertisements in newspapers describe the facility as “a delightful summer vacation spot, with its hotel being a short walk from the Newport News and Mississippi Valley railroad station.” One newspaper article describes Bent as the owner of a local bank and says that he served as the mayor of Mt. Sterling. (Savannah Morning News 1897) Searching the literature does not find the positions mentioned elsewhere. Several newspaper articles state that Bent was a lawyer before acquiring Aden Springs and Park. Bent’s wife, Laura Mitchell Bent, is described in her 1903 obituary in the Mount Sterling Advocate as having worked competently as a bank accountant.

All resources located to date refer to Bent by the initials J. M. – even his obituary. Bent died at the age of 70, after having been bedridden for two days from what the newspaper describes as “locked bowels.” (Mount Sterling Advocate 1907)

Luke Prior Blackburn (1816 – 1887)

REMEMBERED HISTORICALLY FOR HIS VENTURE INTO A “DARK SIDE” OF MEDICINE

Luke Pryor Blackburn, M. D. (1816 – 1887) served as the governor of Kentucky from 1879 to 1883. He was Kentucky-born and a graduate of Transylvania University, earning a degree in medicine. During the Civil War, Blackburn served as a surgeon and was part of Confederate General Sterling Price’s staff. Following the war, Dr. Blackburn earned fame as an epidemiologist, serving as a government agent to control epidemics of yellow fever that broke out in Kentucky, Florida, and Bermuda.

Blackburn was an early visitor to Crouch’s farm and obtained samples of what fell on that strange day in 1876. He distributed portions of what he acquired to others for identification. Following the Civil War, he was elected Governor of Kentucky.

But it is what he did while serving the Confederacy for which he is remembered. The medals bedecking Blackburn’s jacket in the photograph were presented to him by Queen Victoria for his medical assistance in fighting Bermuda’s Yellow Fever epidemic of 1864. The Queen stated that to end the deadly pandemic, “he (Blackburn) fought the good fight.” But the knowledge he gained about saving people from death, he twisted into a plan to kill most evilly. During his tenure treating the sick in Bermuda’s yellow fever hospitals, he collected what he believed to be the most dangerously infectious materials possible. He commandeered the bed linens and blankets from patients immediately after their deaths from yellow fever. Blackburn, aided by a few accomplices, shipped the contaminated blankets through Canada to New York, Boston, and Washington, where they were auctioned to impoverished residents. That part of the plan worked. The blankets were successfully delivered and auctioned.

Fortunately, Blackburn’s understanding of yellow fever’s mode of transmission was wrong. The disease is transmitted to people via mosquito bites, not by contact with clothing from the sick and dying. (That fact was not discovered until 1901 by the U. S. Army physician Walter Reed.) His intention to initiate a yellow fever epidemic in the major cities of the North to force Abraham Lincoln to abandon the war against the Confederacy failed. (McGeary 1865)

Leopold Brandeis (d. 1892) was a lifelong resident of Brooklyn, NY, where he was the proprietor of the Brooklyn Lead Pipe Company. He developed and patented a method for converting brass into a powder that was an efficient brazing material for joining pipes. The brass powder was popular with plumbers and was available only through his company. Brandeis published several articles in the Sanitarian Journal about drinking water quality, sewerage control, and the safety of using lead pipes in buildings. An interesting side note is that Brandeis’s son, Lewis, moved to North Dakota and filed a libel suit against his parents for $30,000. The reason for the claim and its outcome is unknown. (Emmons County Record, North Dakota 04/08/1887)

Prof. Charles Frederick Chandler, Ph.D. (1836 – 1925)

Dr. Chandler received a Ph.D. in analytical chemistry from the Laurance Scientific School at Harvard University. He taught chemistry at Columbia University and became Dean of the Columbia School of Mines. Chandler served as chair of the New York City Board of Health, where he gained public attention for exposing the dilution of milk, known as the NYC milk scandal of 1886. He also investigated and testified on the safety of using water gas as a household cooking fuel. According to the Brooklyn Eagle, on March 10, 1884, Columbia University commissioned a bust of Dr. Chandler by the sculptor J. Scott Hartley for display when they created the Chandler lectureship in chemistry. Additionally, Columbia named their Chemical Museum in his honor. (NY Times May 1, 1910)

Arthur Mead Edwards, D. (1836 – 1914) received a broad education in the sciences. He had the opportunity to study medicine under John Torrey at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, as well as botanist Asa Gray and zoologist Louis Agassiz at Harvard. According to a relative of Edwards on a genealogical website, Agassiz was so impressed with him as a student that he gave him a quality microscope as a gift.

Edwards studied geology, chemistry, and medicine. His first professional position was with the Northwest Boundary Survey as a microscopist under Mr. George Gibbs. Following tenure in that position, Edwards worked with Prof. Josiah Dwight Whitney (1819 – 1896) as a member of the State Geological Survey of California. He then returned to the East Coast to work in geology with Professor C. H. Hitchcock’s team for the state-sponsored Geological Survey of New Hampshire.

Returning to New York City, Arthur founded and served as the first president of the American Microscopical Society and its journal. The publication was the precursor to the Journal of the American Monthly Microscopical Society. (Smiley 1896)

Arthur Edwards taught chemistry and microscopy at the Women’s Medical College, which was associated with the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children. The institutions were founded in 1853 by Elizabeth Blackwell and her sister, Emily. Elizabeth Blackwell is historically significant as the first female physician educated in the United States.

In 1872, Edwards married Emma Cornelia Ward (1845 – 1896). They wedded two years after she graduated from the Women’s Medical College of New York in 1870. Emma worked at the Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children a year after graduating. Hence, the adjacent medical college where Edwards taught is likely the place and reason their relationship developed. After they married, the couple moved to Newark, NJ, and opened medical practices.

According to a biographical article about Arthur Edwards, written by C. W. Smiley and published in an 1896 American Monthly Microscopical Journal issue, Arthur accepted a position to teach chemistry at the University of Tokyo in 1877. The Edwards family, now including two daughters, traveled by train to San Francisco, expecting to continue to Japan by ship. Unfortunately, they did not complete the journey. Arthur developed debilitating memory problems for a reason not mentioned in Smiley’s reporting and canceled the trip. He and his family continued living in the San Francisco suburb of Berkeley for two years. Arthur practiced medicine and became an active member of the San Francisco Microscopical Society.

In 1879, Arthur, Emma, and their children returned from California to Newark, New Jersey. Upon leaving, Arthur donated his books, specimens, and slides to the San Francisco Microscopical Society. Emma reestablished her practice, but Arthur did not return to medicine. Instead, he fully immersed himself in his lifelong passion for natural history and microscopy. (Smiley 1896)

Arthur Edwards was actively writing articles for the journal that would later publish his biography. Since he frequently communicated with the journal’s editor, it is reasonable to assume that Arthur had ample opportunity to correct C. S. Smiley’s version of his life if he felt it was in error or wanted to keep parts private.

The Edward’s Family’s Descendants Version Offers Additional Insight.

The Edwards family’s trip to San Francisco is described somewhat differently on the genealogical website “The Landis Family Tree.” According to Joan T. Hutton (b. 1930), the great-granddaughter of Emma and Arthur, the story handed down through the family was that the Edwards were traveling to Japan so the two could serve as medical missionaries. During the layover in San Francisco, Arthur was attacked and beaten by members of a Tong Gang. The assault caused brain damage that affected his memory and perhaps his personality. During the two years Arthur and Emma lived in Berkeley, they had fierce fights. The problems were not resolved, and the couple stopped speaking to each other, except through their children, who served as interlocutors. (Landis 2022)

Upon returning to Newark, the two separated. Arthur moved in with close relatives on his mother’s side, Harry and Harriet Foster. Emma stayed with the daughters and resumed her medical practice. (Landis 2022)

Harrison Gill (1806 – 1886) married Georgeanne Lansdowne (d. 1883), the daughter of George Lansdowne. The latter was the original owner of the 600-acre property that was to be developed into the Olympian Springs vacation and health resort. Gill worked with his father-in-law to build 30 cabins and a small hotel for those who would enjoy a peaceful summer vacation while bathing in the salty, sulfurous waters seeping from natural springs on the property.

Following the Civil War’s end, the United States Congress passed bill H.R. 2364, the Southern War Claims Act, to compensate for damages done by using and occupying privately owned property by either Union or Confederate Troops. Confederate troops under the command of General Humphreys Marshall were quartered at Olympia Springs. On July 19, 1863, Union and Confederate cavalry fought the Battle of Mud Lick in the area. Part of the warfare ran through Gill’s property. According to the Cincinnati Commercial newspaper, Harrison Gill claimed $7,700 for twelve cottages and several stables at Olympian Springs destroyed by Confederate troops. However, since the damages were caused by Confederate soldiers, the funds would not be paid unless Gill could demonstrate his continuous allegiance to the Union cause throughout the war.

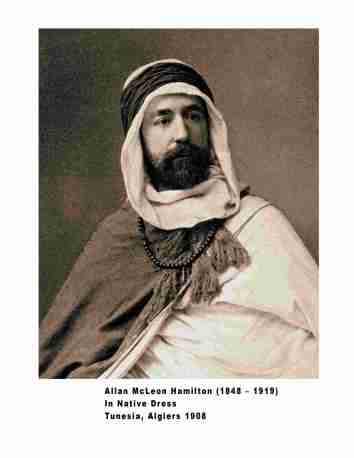

allAn mcClane hamilton(1848 – 1919)

“THE ALIENIST” IDENTIFIES PIECES OF MEAT FROM THE KENTUCKY MEAT SHOWER TO BE LUNG TISSUE

Caleb Carr’s 1993 novel “The Alienist” and the current HBO series revolve around the use of science-based investigations during the late 1800s by a fictional protagonist, Lorenzo Kreizler. Dr. Kreizler is a medical doctor and practitioner of psychology, a field then in its infancy. Kreisler’s particular interest was studying the minds of suffering souls deemed “criminally insane.” A commonly held belief during the 1800s was that mentally deranged person were alienated from their true personalities. For this reason, doctors working with the mentally ill were called alienists.

TV Series 2018 – 2020

Daniel Bruhl, Dakota Fanning, Luke Evans

Daniel Bruhl stars as Lazlo Kreisler

A fictional character apparently inspired by the true-life experiences of

Dr. Allan McCane Hamilton

The most famous alienist of the time was Dr. Allan McClane Hamilton. Dr. Hamilton rose to national fame through his courtroom testimonies as an expert witness in many high-profile criminal cases. In addition, he published the forensic techniques he developed and the legal phraseology other alienists should follow when testifying about a defendant’s mental capacities before a court. The work earned him the sobriquet of “America’s Father of Forensic Psychiatry.” Toward the end of his career, Dr. Hamilton wrote an autobiography titled “The Recollections of an Alienist.” The memoirs he published closely match the personality and activities of Caleb Carrs’ fictional Dr. Kreizler in the current HBO series. For me, watching Daniel Bruhl as the Alienist was a miraculous reincarnation of Allan McClane Hamilton.

Hamilton was addicted to solving mysteries, so when he read about the Kentucky Meat Shower being a mind-boggler, he set out to get his own sample of the evidence. In keeping with his forensic approach, he sought collaboration with a scientist with impeccable microscopy credentials. He chose W. J. S Arnold, a Professor of Histology at New York City University, School of Medicine. Both microscopically examined the samples Hamilton obtained from Charles F. Chandler and agreed that the specimen was a piece of a lung; Hamilton published their findings in the New York Medical Record.

-

-

Louis D. Kastenbine (1830 – 1903) was a physician and chemist. He studied chemistry under the guidance of Prof. Lawrence J. Smith. Kastenbine served in the Civil War, after which he studied medicine at Bellevue Hospital in NYC. He graduated with an MD in 1869, returned to Louisville College of Pharmacy, Kentucky, and began practice in 1872 (Jefferson Evening News 1903), which was most likely the year of his graduation. During his career, he was frequently mentioned in the press, reporting his test results on drinking water quality, food safety, and toxicological testimony presented during several murder trials. Kastenbine received national press coverage for testifying as an expert medical and chemistry witness in several high-profile murder trials. for his court testimonies in criminal trials regarding poisonings. When Kastenbine took the stand before a jury, he described himself as a medical doctor and chemist. Kastenbine was familiar with standards of evidence and cross-examination. Being presented in court as an expert witness —most often a well-paid engagement —necessitated lifelong vigilance over his reputation. One murder trial covered by the N.Y. Times was that of an illiterate farmer who took out a one-hundred-thousand-dollar life insurance policy payable to his wife and then died suddenly. Dr. L. D. Kastenbine examined the body and reported to the court that strychnine was the cause of death. (Times 1897) Kastenbine moved from Kentucky to California in 1903. Kastenbine’s twenty-three-year-old daughter committed suicide in 1912; she shot herself in their home’s upstairs bedroom, after which he disappeared from public view. (Mathews’ 1904)

- Alexander Tennant Parker (1832 – 1922), Lexington, Kentucky. A microscopist who published a short article on archebiosis or spontaneous generation in the Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History. V20 1881. In the article, he reviews the many ways growth media can become accidentally contaminated and, as a result, yield positive growth results. In the last paragraph, Parker concludes that those who claim to have verified their creative power are most likely mistaken. A year later, he published a short article on staining in the American Monthly Microscopical Journal, Vol. 3, 1882, on the staining of aquatic annelid tubes, which was reprinted in the Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society, 1882.

-

John Phin (1832-1913) was a writer, lawyer, and publisher. He founded the Industrial Publishing Company in New York City, which published the American Journal of Microscopy and several other serial publications. Phin was a New York Microscopical Association member and authored the book “Practical Hints on the Selection and Use of the Microscope.” Under his editorship, the American Journal of Microscopy ran four articles discussing the Kentucky Meat Shower.

As the editor of the American Journal of Microscopy, he facilitated the transfer of fallen meat specimens from Crouch’s farm with other microscopists and ran four stories on the Kentucky Meat Shower. Practical Hints on the Selection and Use of the Microscope is a comprehensive guide that covers topics such as the history of microscopes, the different types available, and proper use and care.

The book also provides detailed instructions for preparing and examining various specimens, including plant and animal tissues, minerals, and crystals. Although Practical Hints did not introduce any new information on microscopy, it achieved its goal of serving as an easily accessible guide for novice microscopists.

As editor of the American Journal of Microscopy, he ran four stories on the Kentucky Meat Shower and facilitated the acquisition of specimens from Crouch’s farm for microscopists of established reputation who wanted to examine them firsthand. (West 1886)

The title page of Practical Hints for the Selection and Use of the Microscope

At the top of the page is a dedication to Charles C. Shults written in the hand of and signed by the book’s author, John Phin.

Title page of the first edition of Practical Hints for the Selection and Use of the Microscope.

Dr. Robert Peter (1805 – 1894) was born in England and immigrated to the United States in 1818. He studied medicine at Transylvania University, where he taught chemistry. Peter received an M.D. But practiced medicine briefly. He preferred chemistry and made its instruction his lifelong profession. Peter was a professor of chemistry at Transylvania University during the time the Kentucky Meat Shower occurred.

Prof. Frederic Ward Putnam (1839 – 1915) earned a Ph.D. From the Lawrence Scientific School of Harvard University, where he remained to teach. While there, he became the curator of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Putnam directed excavations across North America and wrote extensively about its native inhabitants. The techniques he developed for unearthing and cataloging artifacts earned him the informal title of the father of American archaeology.

J. Lawrence Smith (1818 – 1893) was a highly respected analytical chemist and meteorologist.

Prof. J. Lawrence Smith, President of the AAAS, 1872.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, March 27, 1880

When the Kentucky Meat Shower event happened, Smith was at the University of Kentucky. He held professorships at several American universities, was elected president of the American Chemical Society, and was a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. His passion was collecting meteorites, and during his lifetime, he amassed, cataloged, and analyzed a fine collection. Smith donated the collection to Harvard University, stipulating that it be kept intact. As a microscopist, in 1850, Smith was credited with designing the first inverted microscope built in the United States. (Silliman 1884)

Thurber, George (1821-1890) Professor of botany and horticulture at Michigan State Agricultural College and editor of the American Agriculturist from 1863 to 1885. He specialized in grasses.

Charles S. Shultz (1839 – 1924) was a 19th-century financier and two-term president of the American and New York Microscopical Societies.

During the 1890s, the state of New Jersey drilled many artesian wells along its southern shores to provide public drinking water. The drillings also provided corings that geologists used to study the strata deposited under New Jersey’s coastal flatlands. After compiling data from many drillings, a cross-sectional map of New Jersey’s subterranean geological morphology, including inclination, thickness, and chemical composition, was created. Microscopists determined the ages of the various strata by identifying the microfossils they contained, primarily by analyzing the silica remains of diatoms. C.L. Peticoles, a diatom specialist, volunteered his time and talents to chemically separate diatom shells from the rock-like cores and then clean and mount them on slides. Dr. D. B. Ward and A. E. Schulze completed the arduous process by identifying hundreds of extinct diatom species. The three researchers built solid reputations as diatom experts over the years they donated to this scientific project.

Schulz’s wise financial investments enabled him to build a posh mansion in Montclair, New Jersey. His wife, Lucy, and son, Clifford, joined him in traveling about the world and finding furnishings that fit the home. What they collected expressed their passions, primarily scientific and archeological artifacts. After the Shultz family died, the Montclair Historical Society kept the Shultz mansion as a museum of nineteenth-century life. Unfortunately, the historical society could not afford to maintain the property, and in November 2021, they sold the building and auctioned off its contents. Shultz had a beautiful mahogany microscope slide cabinet holding five hundred antique preparations. The catalog valued the slide collection as worth between two and three thousand dollars. (I believe this estimation to be low. I do not know the final hammer price, but it should have been more.)

Mahogany Microscope Cabinet Owned by Charles Shultz

From the auction catalog available at: https://www.bidsquare.com/online-auctions/nye/victorian-microscopical-slide-case-2502875

William Henry Walmsley (1830 – 1905) had to end his formal education at the age of eighteen to assume proprietorship of the family’s dry goods business after his father’s death. He developed excellent business skills managing the family business and accumulated enough funds to buy a partnership in the well-established Philadelphia optical company, James W. Queen. Before the professional move, Walmsley studied slide-making with Dr. J. Gibbons Hunt for 5 years. Now, as both an acute businessman and an experienced microscopist, he took over the management of James W. Queen’s microscope department. Walmsley became wholly dedicated to studying biology, microscopy, and the new field of photomicrography. He was a founding member of the American Microscopical Society, a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, a member of the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences, and the University of Pennsylvania Botanical Society.

William Henry Walmsley

Walmsley formed W. H. Walmsley & Co. as an independent company in 1887. The new Philadelphia business primarily dealt with Bausch and Lomb microscopes, slide-making materials, Kodak and Graphlex cameras, and photographic processing chemicals. Walmsley retired in 1903, and the corporation was dissolved.

How to footnote this page

Reiser, Frank W. (2024, February) Kentucky Meat Shower – a new specimen has been found, and it is a lung! Searching an Invisible World for Its Tiniest Things. https://wp.me/PaLJ0g-Wy

References

Arnold, J. W. S. (1882). Microscopical Laboratories, American Monthly Microscopical Journal, Boston, April, p.69.

Brandeis, Leopold (1876) The Kentucky Meat Shower, American Journal of Microscopy and Popular Science, Handicraft Publication, New York, Vol I, p.54 Vol 1 no 5, (reprinted the Sanitarian article)

Chatham Record (1884)

Emmons County Record, North Dakota (April 8, 1887)

The Herald, New York (March 21, 1876) p.4. Available at Chronicling America Newspapers, Library of Congress https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/

Landis (2022) https://landisfamilytree.blogspot.com/search/label/Arthur%20Mead%20Edwards%20-%20Emma%20Ward%20and%20Fosters

Mathews’ Quarterly Journal of Rectal and Gastrointestinal Diseases. (1904). United States: (n.p.).

Maxwell, Tom (2012) “For the Scrutiny of Science and the Light of Revolution,” American Blood Falls. Southern Cultures, Spring V. 18 No. 1, University of North Carolina Press.

McGeary, Francis (1865). The Yellow Fever Plot, The Medical and Surgical Reporter 12/565

Meekins, Christopher A. (2020). Chatham Blood Shower 1884. State Archives of North Carolina. NCPedia https://www.ncpedia.org/chatham-blood-shower-1884 last accessed on 09/10/2020

National Democrat (1912)

New York Times (1876) Flesh descending in a shower, an astounding phenomenon in Kentucky, March 9

Peter, Robert (1890). Geological Survey of Kentucky: Chemical Analysis, E. Polk Johnson, Public Printer.

Phin, John (1876) The Kentucky Meat Shower, American Journal of Microscopy and Popular Science, Handicraft Publication, New York, Vol I, Vol 1 no 6, p.69 (reprinted the Sanitarian article)

Rooker, Henry Grady. (1932) A Sketch Of the Life and Work Of Dr. Gerard Troost. Tennessee Historical Magazine V. 3 no.1

Silliman, Benjamin (1884), Memoir of John Lawrence Smith, Read before the National Academy of Sciences, April 17, 1884, pp 217-236. Available: http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/smith-j-lawrence.pdf

Smiley, C. W. (1896). Sketch of the Life of Arthur Mead Edwards, M. D. The American Monthly Microscopical Journal. Vol. XVIII July p. 226.

The Spirit of the Times, (1841) Blood Rain Falls in Chatham. p 3. No. 1, v18. Leland and Draper, publishers and editors.

Stack County News (1876) Kentucky Meat Shower, Illinois, March 31.

Stevenson, Brian. http://www.Microscopist.net (Best online reference for antique microscope slides)

Venable, Francis P. A Fall of Blood in Chatham County. Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society, Vol I, 1884, pp. 38-40. Available on JSTOR. North Carolina Academy of Sciences

(The Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society was founded in 1883 by Francis Preston Venable.)

West, Charles E. (1886). Forty Years’ Acquaintance with the Microscope and Microscopists. Proceedings of the American Society of Microscopists, V8, pp. 161-173

The Wilson Advance (1984) Shower of Blood Wilson, NC, April 3, V. 14, No. 13, p. 1.Available at Newspaper Archives https://newspaperarchive.com/wilson-advance-may-02-1884-p-2/

Here is a bibliographic-style list of the newspapers that covered the Kentucky meat shower of March 3, 1876, based on the provided references. Entries are organized chronologically by publication date for logical flow from initial reports to later follow-ups and conclusions. Where notes indicate content tone, skepticism, or sourcing (e.g., drawn from the Courier or Herald), they are included. States are standardized for clarity.

- The Evening Post (Ohio). Monday, March 13, 1876, Page 2. (Noted as containing some fabricated or exaggerated content.)

- Richmond Daily Independent (Ohio). Tuesday, March 14, 1876, Page 2. (“Certainly the phenomenon was one of the most wonderful ever known, and doubtless will occupy the attention of the world of science for some time to come.”)

- The Alabama Herald. Thursday, March 23, 1876, Page 1. (“An eyewitness says: Hundreds are willing to attest the truth of the matter with affidavits.”)

- The Times-Democrat (Ohio). Thursday, March 23, 1876, Page 2.

- Nodaway Democrat (Missouri). Thursday, March 23, 1876, Page 2.

- The Daily Commonwealth (Topeka, Kansas). Saturday, March 25, 1876, Page 2. (Skeptical account citing a visitor from Perry, Kansas; defends the New York Herald‘s on-site reporting while noting limited witnesses.)

- The New-Orleans Times (Louisiana). Monday, March 27, 1876, Page 2. (Early report mentioning rumors; notes no state of being seen by Rebecca Crouch, but describes seeing a toe and pieces of meat with a fingernail attached.)

- The Olney Times (Illinois). Wednesday, March 29, 1876, Page 2.

- The Miami Helmet (Florida). Thursday, March 30, 1876, Page 3.

- The Telegraph-Courier (Wisconsin). Thursday, March 30, 1876, Page 7.

- The Courier-Northerner (Michigan). Friday, March 31, 1876, Page 7.

- Muskegon Weekly Chronicle (Michigan). Friday, March 31, 1876, Page 7.

- The Kansas Daily Tribune. Saturday, April 1, 1876, Page 3.

- The Buffalo Sunday Morning News (New York). Sunday, April 2, 1876, Page 4.

- West Point Republican (Nebraska). Thursday, April 6, 1876, Page 1.

- The Independent (Nebraska). Thursday, April 6, 1876, Page 1.

- Chatsworth Plaindealer (Illinois). Saturday, April 8, 1876, Page 2.

- The Hebron Journal (Nebraska). Thursday, April 13, 1876, Page 4.

- Concordia Empire (Kansas). Friday, April 14, 1876, Page 4.

- The Kentucky Gazette. Wednesday, May 24, 1876, Page 2. (Final conclusion article.)